I’m going to partially agree with George Washington law professor Jonathan Turley in his critique of the Democratic case for impeachment. They’ve overcharged the president. But the bulk of this newsletter is going to be about something else entirely—a grassroots revolt that shows the urgent need for the Supreme Court to start setting clear Second Amendment standards. Also, I’ve got a short rant about a new Ninth Circuit case that applies one of the worst legal doctrines in America. On today’s French Press:

-

Don’t impeach Trump for Obama’s legal position.

-

The Second Amendment sanctuary movement’s direct challenge to gun control.

-

Qualified immunity is the absolute worst.

It’s not an abuse of power to assert a traditional legal defense to congressional subpoenas.

I’ve made my position on the House impeachment inquiry quite clear. It’s absolutely impeachable conduct for a president to distort international diplomacy in a strategically vital region of the world to attempt to coerce a desperate, dependent ally into investigating a crackpot conspiracy theory and a domestic political opponent. The president put his own interests above the country—and not in a minor matter. It’s important to set a precedent that such conduct is intolerable.

But in setting a good precedent, the House needs to take care that it doesn’t set a bad precedent—punishing a president for asserting the same legal defenses and advancing the same legal theories that presidents of both parties have advanced for decades.

The House Intelligence Committee condemned Trump for his refusal to grant permission for close aides (like his acting chief of staff and former national security adviser) to testify before Congress. The administration is claiming that these close aides enjoy constitutional immunity from congressional summons. As I explained in a previous newsletter, this is not a fringe position. In 1971, then-Assistant Attorney General William Rehnquist defined the president’s position:

The President and his immediate advisers—that is, those who customarily meet with the President on a regular or frequent basis—should be deemed absolutely immune from testimonial compulsion by a congressional committee. They not only may not be examined with respect to their official duties, but they may not even be compelled to appear before a congressional committee.

Lest you think this was Nixon-era nonsense, long discarded by more reasonable presidents, this opinion was reaffirmed by the Clinton administration in 1996 and by the Obama administration in 2014. As the Obama DoJ explained, this asserted immunity “is rooted in the constitutional separation of powers, and in the immunity of the President himself from congressional compulsion to testify.” Since the president is “the head of one of the independent Branches of the federal government,” if Congress could force the president or one of his “immediate advisers” to testify, then the president’s “independence and autonomy from Congress” would be threatened.

As I wrote just last month, I don’t believe the absolute immunity argument will ultimately prevail—especially in the context of an impeachment proceeding, where Congress is at the apex of its constitutional power. But I’m far from certain in my conclusion, and when administrations of both parties have made a good-faith legal argument in favor of absolute immunity (and when litigation is under way to settle the question) then impeaching a president in part for making an argument he might win at the Supreme Court strikes me as an abuse of the House’s impeachment authority. On this count, I agree with Professor Turley:

A President cannot “substitute—his judgment” for Congress on what they are entitled to see and likewise Congress cannot substitute its judgment as to what a President can withhold. The balance of those interests is performed by the third branch that is constitutionally invested with the authority to review and resolve such disputes.

If the Supreme Court rules against the president, and the president defies the court, add an impeachment count then. Impeach him for the substantive and consequential abuse of power in Ukraine. Don’t impeach him for making a traditional, bipartisan legal argument against congressional subpoenas.

It’s time to pay attention to a grassroots revolt against gun control.

Here’s some news you may not be tracking—dozens of Virginia counties are passing Second Amendment sanctuary resolutions:

Counties across the state of Virginia are passing Second Amendment sanctuary resolutions in anticipation of strict gun control measures planned by the majority-held Democratic Virginia General Assembly.

On Monday, citizens spilled out of the Betty Queen Center in Louisa where an estimated 600 people gathered to pass a resolution that protects the gun rights of Virginians. 41 other counties in Virginia have signed similar resolutions including Appomattox, Bedford, and Lee counties.

While the precise text of the resolutions can vary, you can read a model resolution at the Virginia Citizens Defense League website. Here are the core operative clauses:

That the <COUNTY> Board of Supervisors hereby expresses its intent that public funds of the county not be used to restrict the Second Amendment rights of the citizens of <COUNTY> County, or to aid federal or state agencies in the restriction of said rights, and

That the <COUNTY> Board of Supervisors hereby declares its intent to oppose any infringement on the right of law-abiding citizens to keep and bear arms using such legal means as may be expedient, including, without limitation, court action.

In form and intent, they call back to “sanctuary city” and “sanctuary state” movements in California and other blue jurisdictions. Sanctuary cities attempt to take advantage of constitutional limitations on the ability of the federal government to “commandeer” the use of state or local resources to enforce federal laws by prohibiting state and local officials from actively cooperating with federal immigration officials.

While the legal issues are different (state and local governments are in a different legal posture against the federal government compared to counties confronting their own state officials) the purpose is similar. While the sanctuary language is carefully crafted as a declaration of intent rather than an enforceable rule—the intent is still quite clear. If the state wishes to pass expansive new gun control laws, it can’t count on local authorities to enforce state edicts.

The Washington Free Beacon’s Stephen Gutowski (flat-out one of the best journalists in America covering Second Amendment issues, by the way) interviewed Virginia Citizens Defense League president Philip Van Cleave. Van Cleave said that resolutions had bite:

“It’s more than symbolic,” Van Cleave said. “It can affect the employees of the county. So, you’ve got a county police force. If the employees are breaking this policy, they can be fired.”

The immediate cause for the wave of sanctuary city resolutions was SB 16, a proposed state Senate bill that would ban not just the sale or transfer of so-called “assault firearms,” but their possession as well. Its passage as written would could render millions of otherwise law-abiding citizens felons unless they surrendered their firearms. The Second Amendment sanctuary resolutions (often passed after public meetings in front of overflow crowds) represent a show of brute political force, a warning that a new law would essentially be a dead letter in vast sections of the state.

But there’s a larger proximate cause of the Second Amendment sanctuary movement (a movement that extends well beyond Virginia)—the Supreme Court’s retreat from Second Amendment jurisprudence after Heller and McDonald. Those two cases established that the Second Amendment protected an individual right to keep and bear arms and held that state and local governments were bound by the Second Amendment. But then the court fell silent, and it’s been silent for almost a decade.

Lower courts have rushed to fill the jurisprudential void, and the result is a crazy-quilt of competing doctrines that’s unlike any other arena of constitutional law. A law-abiding citizen can immediately become a felon simply by driving from a county into a city, or from one state to the neighboring state. Legislators draft gun-control legislation—and apply criminal penalties to that legislation—without any real understanding of the limits of their power.

And just as there exists a crazy-quilt of competing laws, there is a crazy-quilt of competing constitutional theories. Second Amendment sanctuary rules require local officials to interpret the constitutionality of state laws. Does the Second Amendment permit an assault weapons ban? We don’t truly know. The Supreme Court has denied certiorari in cases appealing assault weapons bans, but language in the Heller decision cuts against such bans. Does the Second Amendment permit gun confiscation of lawfully-purchased firearms. We don’t know. Does it permit bans on standard-capacity magazines? We don’t know.

Here’s an even more basic question. What kind of constitutional test should we apply to gun control legislation? Intermediate scrutiny? Strict scrutiny? Something else? We don’t know.

I’m a federalist, and that means that I’m strongly inclined to defer to local authority. For example, I don’t agree with sanctuary city policies, but I believe that federalism requires deference in the use of state resources. I like to see states adopt different economic and environmental policies in accordance with the different values and priorities of their different populations. Let California be California and let Tennessee be Tennessee.

But federalism ends where the Bill of Rights begins. The civil liberties protected by the Bill of Rights represent the core “privileges and immunities” of American citizenship. The only discretion states, counties, and cities have is to grant greater protection than the Bill of Rights requires. While states can set a higher ceiling to your rights, they cannot go below the federal constitutional floor—there is a set of strong First, Fourth, Fifth, and Sixth Amendment protections that follow me no matter where I fly or drive in this great land.

Not so with the Second Amendment. States can (and do) set high ceilings, but under current Second Amendment jurisprudence, it seems that they may be able to set very, very low floors—so low that that many jurisdictions take the position that the only clearly protected Second Amendment right is the right to possess a handgun in my own home for self-defense.

A core individual liberty protected by the Bill of Rights should not be so poorly defined. From assault weapons bans to magazine restrictions, we know the core issues. The nation needs clarity, and until it gets clarity, we’ll see increasing volatility around one of the most consequential and polarizing issues of our time.

I can’t even with qualified immunity.

In Tuesday’s newsletter I wrote briefly about an issue that I addressed numerous times at National Review—how qualified immunity helps bad state actors escape accountability for their unconstitutional acts. It’s an entirely judge-made doctrine that contradicts the plain language of federal civil rights statutes. The Supreme Court reinterpreted the words “shall be liable” in 42 U.S.C. Section 1983 to mean that state officials are not liable for violating the civil rights of citizens “insofar as their conduct does not violate clearly established statutory or constitutional rights of which a reasonable person would have known.”

And what is a “clearly established” right? Is that so onerous to prove? After all, the Bill of Rights contains a collection of clearly established rights. But no. As the doctrine has developed, to prove that a right is clearly established, the plaintiff generally has to find and cite a remarkably similar case, with nearly identical facts, decided by a court of controlling jurisdiction.

This has led to absurd results. In Florida, a police officer enjoyed qualified immunity after knocking on the wrong house, without a warrant, failing to identify himself as a cop, and shooting an innocent man dead in his own home. In Tennessee, qualified immunity protected an officer who sicced his police dog on a sitting, surrendered criminal suspect who had his hands in the air. I could go on and on and on.

In fact, I will go on. On Wednesday the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals created a fresh judicial outrage (hat tip to Gabriel Malor, who spotted the case) when it granted qualified immunity to police officers who “reveal[ed] a domestic violence complaint made in confidence to an abuser while simultaneously making disparaging comments about the victim in a manner that reasonably emboldens the abuser to continue abusing the victim with impunity.”

Here’s the kicker, the alleged abuser was a police officer. Cops disclosed a complaint to a fellow officer and mocked the victim to her alleged abuser. But they received qualified immunity anyway. Why?

[The defendants] are entitled to qualified immunity because the due process right conferred in the context before us was not clearly established. Although the application of the state-created danger doctrine to this context was not apparent to every reasonable officer at the time the conduct occurred, we now establish the contours of the due process protections afforded victims of domestic violence in situations like this one.

Translation—you can get away with violating the plaintiff’s rights just this one time. Do it again, and you’re in real trouble.

That’s not the way the law is written. That’s not the way the law is supposed to work. That’s not justice. A bipartisan coalition of civil rights groups (including my old colleagues at the Alliance Defending Freedom) has pressed the Supreme Court to reverse its judge-made doctrine and apply the text of the statute. So far, the Supreme Court has stood firm in defense of its misbegotten precedent. May that soon change.

One last thing …

The tweet below is a test. The only way you understand its brilliance is if you spend way too much time on Twitter. I do, and it’s hilarious:

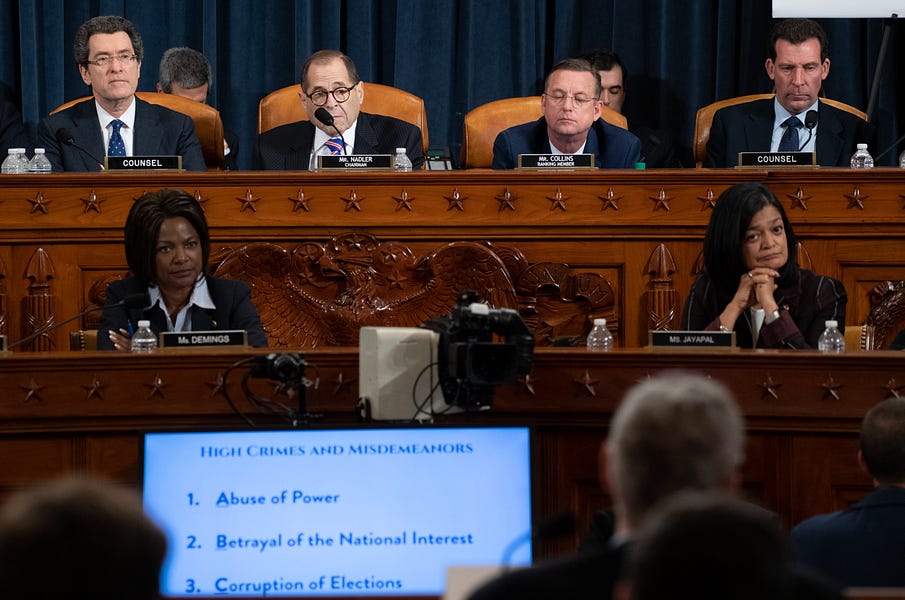

Photo credit: Members of the House Judiciary Committee listen to testimony in the impeachment inquiry against Donald Trump December 4, 2019. (Photo by Saul Loeb-Pool/Getty Images)

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.