Kyle Rittenhouse, Open Carry, and the Breaking of Self-Defense Law

Earlier today I published a piece over at The Atlantic that makes two arguments. First, Kyle Rittenhouse wasn’t a hero. He was remarkably foolish to grab a rifle and insert himself into Kenosha’s unrest. He had no business walking into that fray. Second, his foolishness did not eliminate his right to self-defense.

At a surface level, these assertions are both common sense and legally quite basic. American self-defense law is relatively simple and easy to understand. While there are state-by-state permutations and subtleties, it goes something like this:

If I’m attacked, absent a duty to retreat (which doesn’t exist in all jurisdictions and is subject to its own limitations), I can respond with proportionate force sufficient to address the threat. If someone punches me, I can punch back.

At the same time, regardless of the kind of weapon used against me (even if it’s just fists), I can use deadly force if I reasonably fear that I face imminent death or grave bodily injury.

I cannot, however, initiate a violent encounter and then use deadly force whenever that encounter goes badly. Good luck claiming self defense if you start punching someone and then kill them when you believe they’re gaining the upper hand. If you’re going to use deadly force, you have to first do all you reasonably can to end the encounter.

The Wisconsin self-defense statute—the key statute at issue in the Rittenhouse trial—is representative of these principles. Here are the key provisions. First, the general statement:

A person is privileged to threaten or intentionally use force against another for the purpose of preventing or terminating what the person reasonably believes to be an unlawful interference with his or her person by such other person. The actor may intentionally use only such force or threat thereof as the actor reasonably believes is necessary to prevent or terminate the interference. The actor may not intentionally use force which is intended or likely to cause death or great bodily harm unless the actor reasonably believes that such force is necessary to prevent imminent death or great bodily harm to himself or herself.

And second, here’s the caveat regarding provocation:

A person who engages in unlawful conduct of a type likely to provoke others to attack him or her and thereby does provoke an attack is not entitled to claim the privilege of self-defense against such attack, except when the attack which ensues is of a type causing the person engaging in the unlawful conduct to reasonably believe that he or she is in imminent danger of death or great bodily harm. In such a case, the person engaging in the unlawful conduct is privileged to act in self-defense, but the person is not privileged to resort to the use of force intended or likely to cause death to the person’s assailant unless the person reasonably believes he or she has exhausted every other reasonable means to escape from or otherwise avoid death or great bodily harm at the hands of his or her assailant.

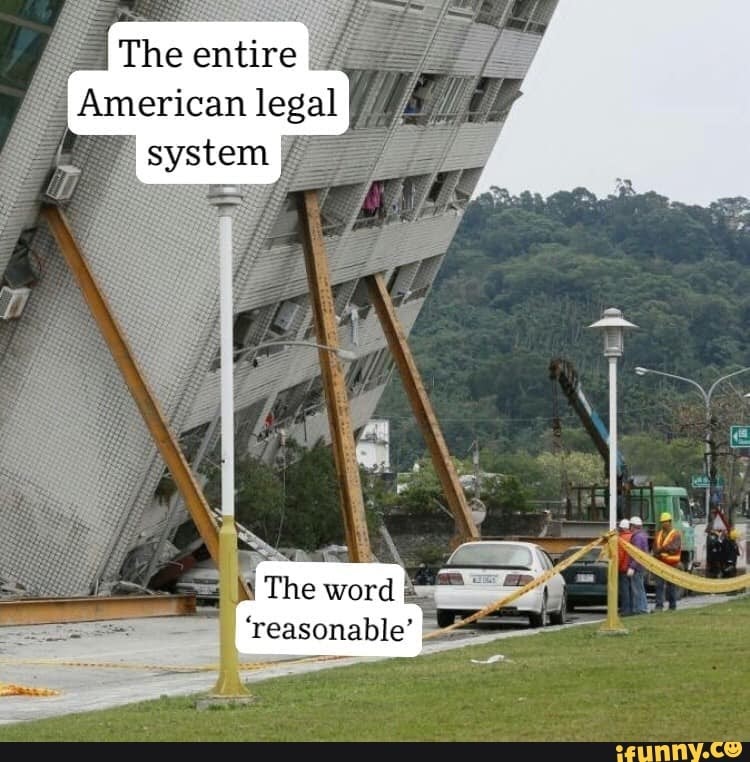

Now, here’s the pop quiz for both lawyers and non-lawyers. What is the key word in both sections? I’ll give you a hint from a popular legal meme. (Is that a thing? Can a legal meme be popular?) Here it is:

The core question in a fatal self-defense case is whether the person’s sense of mortal threat was “reasonable.” That’s a word that’s hard to define, and juries often quite simply punt.

Prime examples of punting are found in jury responses to police shootings. Clever defense lawyers present evidence that the cop was afraid and then ask, “Who are you, sitting in a comfortable chair, to second-guess a split-second decision?”

The answer to this question is, “We’re a jury, compelled by law to sit in this chair and second-guess split-second decisions.” Instead, juries often simply acquiesce. The officer was afraid. He puts his life on the line. Who am I to sit in judgment?

But this brings me to the Rittenhouse trial. While there is intense debate over the specifics of each shooting, there also needs to be serious attention to one of the underlying realities of not just that fatal night in Kenosha but also of volatile protests and public confrontations in general—the increased prevalence of open-carried rifles (mainly AR-15s).

The presence of angry, openly armed men dramatically increases the sense of danger surrounding any public confrontation, and then it entrusts other angry (often) armed men to understand exactly when menace transforms into deadly threat.

There are bright lines—such as when someone points a gun directly at you. But by that time it can be entirely too late to take any meaningful action to save your life. What if someone advances toward you with a weapon at the low-ready, with the weapon slightly raised but still pointing down? What if they’re approaching your home? Does the “reasonable” man wait for gunfire?

Public peace thus rests in the snap judgments of untrained men and women in times of extreme stress. We’re extraordinarily fortunate that we’ve not had more incidents like the dreadful events the night of August 25, 2020, in Kenosha.

Yet rather than sobering public minds or cooling the public temperature, the Rittenhouse trial seems to be inspiring a wave of admiration. An increasing number of right and left-wing individuals and groups are resorting to open carry as a matter of course. In some quarters it’s seen as a sign of manliness. Here’s one example:

Here’s another:

What is to be done? The text and history of the Second Amendment permit a person to both “keep” a weapon at home for self-defense but also to “bear” a weapon outside the home for the same purpose. But the history also indicates that early gun regulations could restrict the ability of a person to cause “fear” or “terror” with their weapons, or to go armed “offensively.”

How does a government protect against “fear” or “terror” while also respecting the right to “bear” arms? How does it dial back the tensions that could cause “reasonable” people to be more apt to feel mortal fear and react accordingly? It can tightly restrict open carry.

As I wrote in The Atlantic, there is an “immense difference between quiet concealed carry and vigilante open carry, including in ham-handed and amateurish attempts to accomplish one of the most difficult tasks in all of policing—imposing order in the face of civil unrest.”

At the same time, however, it’s incumbent on the government to do its best to maintain order, lawfully and constitutionally, so that there is no perceived need for vigilantism. Responding to riots is remarkably difficult: When violence explodes we can’t reasonably expect law enforcement to immediately impose peace, but obvious police negligence or permissiveness is itself destabilizing.

Yet it’s a mistake to believe that open carry is always tied to out-of-control unrest. It’s become part and parcel of all too many protests, including anti-lockdown protests and election protests, even at public officials’ homes.

There is no credible argument that this form of open carry is “self-defense.” It’s intentional intimidation.

I am the last person to argue against effective, armed self-defense. I exercise my Second Amendment rights to both keep and to bear arms. I’m loath to delegate my responsibility to protect my family entirely or even mainly to the state. But I completely reject the notion that I have a right to intimidate my fellow citizens. I don’t have a right to use my weapons to make them afraid.

After the jury renders its verdict for or against Rittenhouse, it will be time to change the debate. As American politics becomes increasingly polarized and increasingly vicious, it’s time to fundamentally rethink open carry, both as a matter of ethics and a matter of law.

One more thing …

The Expanse. Season 6. It’s happening. Here’s the trailer, just hours old: